Analysis of the importance of cultural fit in the alliance between Accor and Huazhu

February 5, 2022 2022-02-05 20:02Analysis of the importance of cultural fit in the alliance between Accor and Huazhu

Analysis of the importance of cultural fit in the alliance between Accor and Huazhu

Managing global alliances – 25-7D07-00S-A – Sheffield Hallam University | Sheffield Business School.

Need a paper like this one? Get in touch via the order form or chat with us via our social media channels.

Introduction

In the words of Prashant and Harbir (2009), strategic alliances present pure paradox to firms. This is as attributing to the fact that one hand they present an unmatched opportunity for growth and expansion while on the other hand they are predominated with conflicts of interest between different parties involved. Further they are known to bear very little success rates. According to a research done by Kavanamur and Esonu (2011), culture is an imminent issue in strategic alliances and cannot be downplayed as a macro-environmental issue. This is because culture affects the performance of alliances directly. As to establish the actual importance of being attentive to cultural issues, this report seeks to inquire into the importance of cultural fit in the alliance between Accor and Huazhu Hotel Group.

Accor is a group of hotels founded and operational in France. On the other hand, Huazhu is a multinational group of hotels that has been dominant in operations in the Asia regions including China. Both firms run hotels in the hospitality industry – a sector that has seemingly a large potential for growth (Ernest and Young, 2015). This report will analyse the benefits from the end of Accor Hotels with keen interest to the investments done in partnership with Huazhu in the Chinese market. In order to achieve this, the report will critically evaluate the management of cross-culture in strategic alliances then analyse the importance of cultural fit in international alliances.

Critical evaluation on the methods of managing cross-cultures that influence strategic alliance

Critical Evaluation of Patterns of Cultural Difference

As established in the introduction, strategic alliances are faced by different problematic situations including dire failure rate. Okoro (2013) notes among these issues are communication problems that necessitate managers at all levels of the organisation to be wary and sensitive to communication aspects. Okoro (2013) further emphasizes on the imperative nature of communication especially in cross-cultural and multinational alliances noting that it is the core of cross-cultural business negotiations. Both domestic and foreign managers need to have an understanding as to the communication implications of working with people from divergent cultures. Such knowledge by managers – especially bicultural managers – according to Hong (2010) establishes ample platforms on which business activities run smoothly.

Wang (2009) has done a study on communication patterns between the Chinese and Americans – western countries – in the realms of high context (based on body language) and low context communication (based on verbal cues). In his findings he notes that having awareness of both high context and low context culture gives an individual a broader perspective of issues. Similarly, it lessens the chances of conflict as well as smoothing up communication. Okoro (2013) addressing the downside of cross cultural communication notes that failure in communication is what has directly influenced failure in alliances rather than professional incompetency. This is due to misunderstandings and miscommunications issues as Brown (2009) posits.

Besides the major cultural issue in strategic alliances is communication. The cultural backgrounds of individuals also affect their approaches to issues of conflict resolution, team engagement, a directness in their communication and aspects of hierarchy and power. On attitudes towards conflict for example, Samovar and Porter (1994) notes that there are cultural conflict assumptions that are linked to a particular culture. In collectivist and high communication context societies, conflict is viewed as damaging to the social face and thus needs to be avoided. Similarly, is considered too dysfunctional and indicates lack of self-disciplines and censorship on those negating in it. The prevalent way of dealing with conflict in such societies is through discreet and subtle means and ensuring a win-win face reputation. However, in individualistic societies with low context communication habits, conflict is seen as constructive and necessary in building relationships. Samovar and Porter (1994) conclude that individualistic and low context negotiators in business tend to be problem oriented and focus of definition and solutions of problems as opposed to collectivist oriented leaders who focus on relationships and saving face.

Differing approaches also influence the directness in requests and communication aspects. Ogiermann (2009) for example critics the indirectness in collectivist society communications noting as it creates the effect of “evasiveness and manipulative behaviour”. It raises questions as to the availability of the information being sought. Salleh (2005) notes that although indirect communication befits informal communication contexts, in business negotiations, directness which is associated with western leadership styles is helpful in maintain low context conversations and addressing negotiations objectively. Ferraro (1998) adds important aspects to cultural patterns affecting strategic alliances. He makes a reference to the fact that Hofstede’s frameworks finds Asian cultures as having a high power distance ascription which makes them respect power and those in authority more (Kawar, 2012). Ferraro (1998) exemplifying this by averring that in Japanese firms decisions have to go through the entire hierarchy of the firm before approval; this is a sharp contrast to western nations where equality is more emphasized.

Managing Cultural Diversity in an Alliance

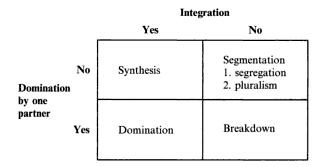

In the above section there are issues that have emerged as imminent in strategic alliances and that to a great extent affect the success rate of the alliance. Issues related to communication, decision making, conflict resolution, directness and hierarchy are influenced by cultural backgrounds and as much as personality traits. As such, it is paramount for managers of cross-cultural teams to apply methods that are integrative and considerate of all cultures involved and in the process ensure synergetic effects (Bird, 2013; Ji, 2012). There are various approaches to management that result in a cultural fit. This report discusses dominance, synthesis, breakdown and segregation as posited by Davies, Nutley and Mannion (2000) in their study on cross-cultural diversity management. The approaches to managing cultural diversity are summarised in figure 1 below.

Domination

According to Davies, Nutley and Mannion (2000) and Child et al. (2005), domination is undertaken in a strategic alliance in the event where there is consensus that both cultures cannot integrate in any way and thus one is made dominant. Lincoln (2009) exemplifies this concept of dominance by using multinationals in Japan. The main critic in his work is that Japanese firms in the event they team up with western firms; they become too dominant hence ending up with the bigger share of value from the alliances. However, Lincoln (2009) notes the upside of this dominance is that it helped uplift most of the failing alliances. Examples of alliances where Japanese firms were dominant are Fukurawa and Siemens, Borden and Meiji Dairy and Sumitomo and 3M.

Synthesis

Child et al. (2005) define synthesis as the scenario where both cultures in a strategic alliance are incorporated – melded. Davies, Nutley and Mannion (2000) refer to synthesis as synergy noting that only the beneficial elements are sieved through the melding process and thus ensuring only positive attributes are employed in the alliance. In his dissertation, Clerc (1999) emphasises the need for cultural synthesis in a merger as a way of creating sustainability. Exemplifying using the merger between Renault and Nissan (French and Japanese cultures), Clerc (1999) elaborates the concept of acculturation which helps in achieving positive results. – Synergy.

Breakdown

Van Marrewijk (2004) refers to the breakdown strategy where one partner gets to dominate the culture of the alliance but without the will of the other partner. Child et al. (2005) maintains that the breakdown strategy is never a solution because it puts and end to cooperation. This especially happens when employees of the ‘inferior’ culture blatantly relegate focus on their duties and responsibilities and hiding behind cultural issues. The different groups represented are incapable of working together as long as the alliance exists. However, Van Marrewijk (2004) considers the appropriateness of the breakdown strategy in the event that there is necessity of studying cross-cultural resistance by looking at how different groups interpret their environment.

Segregation

Child et al. (2005) defines segregation as the process where a balance is stricken between the partners involved in a strategic alliance. The needs of the different cultures are balanced rather than integrated for synergy. Mannion et al. (2011) on the other hand notes that there is a upside to the segregation approach as it is more suitable in the cases where complete cultural integration is impossible. The same is exemplified by the case of LIFT (Local Improvement Finance Trust) in the department of health. The organisation applies segregation in the event of failure of complete integration. Williams (2012) also adds that segregation is a sure way of avoiding cultural conflicts among other culture management issues. This approach does however slim chances of intercultural synergy and learning.

The Importance of Cultural fit in International Alliance

Cultural fit is defined by Rivera (2012) as the possibility that a new employee will fit into the culture prevalent in an organisation. Further, Rivera (2012) avers that cultural fit has become a convergent point for contemporary workplace hiring and that it influences the choices that interviewer make regarding the best candidate. Hill (2013) notes for example a certain manager in a Tech firm hired an employee not because of the professional prowess in the interviewee background but because of the shared rapport during the interview. The perspective of this manager was that as long as the employee fit in the culture of the firm she could be trained on other aspect. These sentiments are supported by Casserly (2013) who note on the importance of cultural fit in general and even for start up companies that managers would trade off qualifications for it.

In the case of international alliances, the concept of cultural fit is more elaborated since the culture extends to external background and macro-environmental culture as opposed to organisational culture only. Pitt, van Werven and Price (2011) while addressing the life cycle of strategic alliances insist on the importance of attending to cultural fit issues as early as in the formation stage of an alliance to avoid crumbling and stalled performance in the last mature stages of the alliance. Kavanamur and Esonu (2011) emphasize the need for cultural fit management in alliances between the western firms and firms in developing nations.

Human Integration

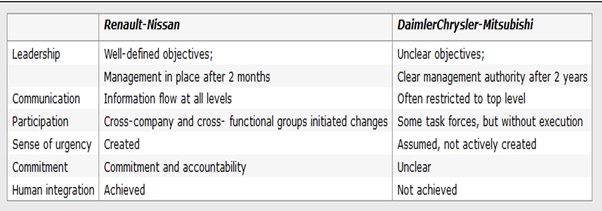

There are differing approaches that firms used to maintain culture fit. One of the main factors imminent in alliances is the integration of employees and individual organisational cultures. Thusly, the element of managing human integration has become important. This extends to the ends of employee synergy, ease of communication, avoidance of conflict et cetera. Undeniably, human integration is a prerequisite to the success or failure of an alliance. This factor is evidenced in the study by Froese and Goeritz (2007) where they investigate the human and organisational integration and the impact on an alliance. The case studies are between the Nissan-Renault merger and the DaimlerChrysler-Mitsubishi acquisition. The specific elements of human integration that were investigated include communication, leadership, employee engagement, sense of urgency and commitment.

In the case of Nissan and Renault the above attributes were well observed. Firstly, in an interview with the wall Street Journal, the CEO of the Nissan-Renault alliance Carlos Goshn notes that the integration and understanding of employees in the fimr has helped strengthen the alliance (WSJ, 2015). In Japan he notes that instructions from the top are easily followed by subordinates while this is not the case in ‘Latin environment’ such as France. Thusly, people are treated differently depending on their background. Guthrie (2012) notes that Goshn is a well respected figure in the alliance having a participatory leadership style characterised by definite objectives. His participatory style was evidenced when he joined the firm and immediately started introducing himself to people and asking for their ideas. Further he set a goal of making profits for Nissan within two years- which he attained. Guthrie (2012) adds that Goshn respected the Japanese culture and even brought changes to accommodate Japanese employees. Froese and Goeritz (2007) in regard to the alliance note that at the beginning Goshn formed a committee to oversee the merger through a synergy effect. In addition a cross-cultural team consisting of five managers from both sides serving at different levels was formed and would meet monthly to oversee progress.

In contrast in the DaimlerChrysler- Mitsubishi alliance, DaimlerChrysler relied on its own staff to make decisions in the alliance. The main exception was the research and development department where the teams from both sides worked together. The rest of the alliance did not have clearly defined chain of responsibilities as well as command. Froese and Goeritz (2007) notes that although there were laid down procedures for the alliance, both parties never bothered to communicate or enforce them. The Mitsubishi managers had hoped to learn from their DaimlerChrysler counterparts but they got treated as junior as no Japanese manager was involved in the making of top decisions. In addition Froese and Goeritz (2007) avers that decisions were only communicated to division heads which means the subordinates were entirely left out as decisions rotated at the top management. This was a ‘target-specific’ policy on information. Further there were not set objectives with the only concern being short term profits which led to crumbling of the set cross-cultural projects for integrating employees. The figure below summarises these facts.

Integration of Organisational factors

As evident in figure 2, the success of the Nissan-Renault merger emerges from the achievement of human integration. This alliance has been praised as the longest-standing alliance and an empire that exemplifies the most complex management style available (Dumaine, 2014). As evidenced in these mergers, the extent to which a management is willing to attain cultural fit is important as it strategically determine the results of an alliance. Froese and Goeritz (2007) extrapolates the idea of strategic alliances and culture further by suggesting that human integration and its antecedents are not the only issues of consideration, organisational factors as affected by culture also matter. This is well evidenced in the attempted merger between BenQ – a Taiwanese firm – and Siemens – a German owned firm.

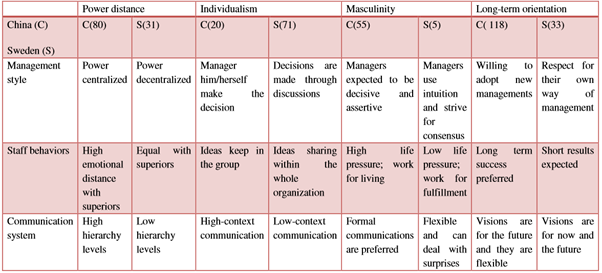

Cheng and Seeger (2012) in their case study on the attempted merger between BenQ and Siemens highlight the main cause of failure in the merger as lack of proper cultural integration hence lack of the synergy effect. What Cheng and Seeger (2012) suggest is the proper understanding of a nation’s culture and an organisation’s culture before attempting any merger. This is better attained through the framework developed by Hosftede. To exemplify this, figure 3 below depicts the findings of Hofstede analysis between Sweden and China which is are representative of western and eastern cultures respectively. The findings are drawn from the study by He and Liu (2010) on cross-cultural communication factors that are affecting Swedish companies with subsidiaries in China.

The findings by this study conducted by He and Liu (2010) suggested that the understanding of cultural fit is important in ensuring that there is adherence to such a model by Hofstede. Reverting to the alliance between BenQ and Siemens mobile division, the alliance was born out of a miscalculated move by a major Taiwanese electronics manufacturer BenQ. BenQ was to benefit from the alliance in terms of gaining a global supply chain that had initially belonged to the Siemens mobile. On the other hand Siemens was benefit by tapping into the investor confidence restored after doing away with a less profitable mobile phone segment. As established above, the major threat to this alliance was the understanding of culture.

According to the findings by Cheng and Seeger (2012), the European Germanic culture offered more room for individualism, power equality, more future oriented and more assertive in decisions. On the other hand, the Taiwanese Confucius culture was more of collectivism, high power distance, less future oriented and more rule-oriented. This aspects of culture difference as established using the Hofstede model impact on organisations culture in terms of leadership style, communication and general employee conduct (He and Liu, 2010). The CEO of the BenQ firm was a Taiwanese and as much embraced the culture of collectivism. This led to the Siemens subsidiary being brought in without changes in the management as the BenQ end of management hoped for harmony and peace that would see smooth operations (Huang and Sun, 2006). In the event of this ‘wishful thinking’, the management of the alliance saw over six management changes in the period of starting operations (Einhorn and Reinhardt, 2005). Collectivism generally dictates a utilitarian approach with much interest paid to in-group members. The lack of radical action by the management saw the collapse of the alliance. Further the chairman Y.K. Lee tried to resign but due to the high position accorded to him by Taiwan stakeholders he was kept on course as they culturally had confidence in him. This also contributed to the failure of the alliance.

Another element of cultural clash the compromised cultural fit for the alliance was in terms of certainty and risk taking. Cheng and Seeger (2012) note that in the initial year of operation of the alliance, the BenQ end faced losses running up to $36.7 billion and because the management was mostly Taiwanese, they kept their cool. This is based on the fact that the Confucius culture is known to avoid uncertainty and perseverance towards results. However a continuation of loss was met by a discarding move when the alliance was dissolved as a wya of avoiding uncertainty. Woodsworth and Penniman (2013) insist that the undermining of the influence of culture and hence ignorance of cultural fit for the alliance led to its collapse. They also note that internal communication was crippled and if it had been strengthened then employees would have less uncertainty and fear and consequently less turnover for the alliance. Cheng and Seeger (2012 further believe that the Siemens end of employees were used to formal and structured approaches to work while the Taiwanese employees were used to rule-oriented approach and a much informal environments. Germans and prowess and followed rules to the book while the Taiwanese employees were more flexible and relegated in their work approach. Woodsworth and Penniman (2013) liken the BenQ-Siemens alliance with the DaimlerChrysler- Mitsubishi alliance in that in both of them the influence of cultural issues and cultural fit in management was downplayed and resulted in catastrophic losses.

It is imperative to note that when an alliance has intercultural management under control, the benefits are phenomenal and this is the advantage enjoyed by through cultural fit. An example of a an alliance that proved successful despite cultural struggles is the EADS (European Aeronautic Defence and Space Company) resulting from a merger between the French firm Aerospatiale-Matra, the German firm DASA and Spanish CASA. The EADS management was faced with the humongous task of transcending culture between the three organisational and national cultures in Spain, Germany and France. The approach used by the management as per Barmeyer and Mayrhofer (2008) is a balance and integration of the teams from all the countries. Rainer Hertrich a CEO to one of the groups notes that in order to achieve a cultural fit, the areas addressed were the organisation, the corporate culture and human resource management. Symmetry at the managerial level was ensured in order to attain an equal distribution of capital between France and Germany. This symmetry approach led to the appointment of two interim presidents French Philippe Camus and the German Rainer Hertrich. Additionally, the French side manages the Airbus and Space division, the German side manages the Aeronautics, civil systems and defence divisions and the Spanish side manages the Military transport airplanes. The headquarters is divided into two units the strategy and marketing headed by the French in Paris and the finance and communications headed by the Germans and located in Munich. The managers heading the divisions are appointed from different nationalities to ensure a balance in the cultures.

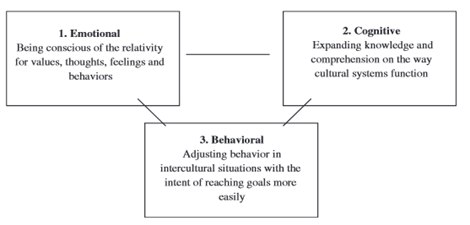

Barmeyer and Mayrhofer (2008) further note that in order to make cultural integration work, EADS appointed a team of 80 experts to facilitate cultural integration through human resource strategizing. The result is that the employees were reshuffled and shifted to different divisions as well as hiring of 1500 additional staff from diverse cultures. The aim of this was to achieve creativity and a new level of group dynamics including synergy. Additionally, mono-cultural teams were entirely replaced with bi- or tri-cultural teams and were used to foster learning and development. The process initially triggered culture shock but eventually got characterised with learning, discoveries and endless amazements. Lastly, to avoid cross-cultural communication difficulties, English was made the only official language in all the divisions. The team synergy and cultural fit benefits attained include the making of the Airbus A340. The various parts used were manufactured as a result of great teamwork from the players involved. Despite the upsides that EADS achieved, there are drawbacks similar to those of other mergers bordering on culture and leadership. To counter this, the EADS group created a system to achieve cultural and leadership harmony – the CBA (Corporate Business Academy) University. This institution achieved success in the training of staff on traversal relations with multiple cultures, management and leadership functions. Intercultural learning thus was a key part of the EADS merger.

In summary, the concept of cultural fit is invaluable in the management of strategic alliances. As seen in the above examples of strategic alliances, mistakes made such as undermining the impact that culture has on a firm’s strategic direction is catastrophic, the loss such as in the case of BenQ and Siemens could run into billions of money. In dire cases, the closure of the firms is necessary to stop further deterioration of such situations. Benq and Siemens had to close down on account of insolvency. In cases where cultural fit was achieved such as in Nissan-Renault alliance and EADS, the results are fulfilling as both profits and scale of operations expand enormously.

Conclusion

The intent of this report was to investigate the importance of cultural fit in the Accor and Huazhu hotel groups. These are hotels from different cultural backgrounds, that is, France and China respectively. In the first section of this report shows that there are various imminent problems associated with cross-cultural strategic alliances ranging from communication, hierarchy issues, promptness, conflict aspects et cetera. Similarly, there are different managerial approaches to diversity in an organisation inlcuidng dominance, synthesis, breakdown and segregation. The second section evidences that the application of different approaches leads to different consequences and the most relevant is that ignorance of culture results in failure of an alliance. The BenQ-Siemens alliance and the Chrysler-Mitsubishi alliances failed due to disregard and underestimation of the power of culture on the alliances. On the other hand the EADS alliance and the Nissan- Renault alliance succeeded because of proper planning and observance of cultural fit. This is besides the fact that some alliances such as EADS face more than three cultural perspectives. It is thus conclusive to posit, as established in the introduction, cultural fit is invaluable in the management of strategic alliances.

Recommendations

Accor and Huazhu, just like the alliances exemplified within the paper, seek to join forces in order to expand their operations in the respective countries, that is, China and France. The hotel and hospitality industry in China is growing and this Accor is bound to benefit from the growing industry in China. Imminent issues in this alliance include intercultural communication conflicts, organisation management styles, resolution of conflict, teamwork and related cultural issues. In light of the theories and examples in this report, the following recommendations are made for the alliance between Accor and Huazhu. Firstly, in order to better grasp the cultural issues prevalent in the merger, a cross-cultural compatibility study needs to be conducted. To guide this, the report recommends the Hofstede’s framework of cultural study which encompasses the relevant elements. Secondly, the organisational culture in both institutions needs to be investigated and the extent to which the national culture impacts on the organisational culture. The next step needs to the harmonisation fo both cultures to reduce the cultural conflict that are resultant of the merger. To acieve this, as in the EADS merger and Nissan-Renault merger, Accor needs to appoint a team to oversee the process. The paramount point in this is that both cultures need to feel respected and engaged. In order to avoind pitfalls of BenQ-Siemens and Chrysler-mitsubishi, it is important that the management of Accor and Huazhu to develop clear objectives for the alliance. This could be as in the case of Carlos Goshn the CEO of Nissan-Renault alliance who set target for profit improvement in two years among other goals. Additionally, clear communication should be made to all stakeholder so as to, one, keep the employees from both sides engaged and, two, allow for rational decision making. This will avoid a similar case as that of Chrysler and Mitsubishi where Japanese managers were down-looked and kept out of the loop. Finally, stringent measures regarding cultural integration need to be observed such as creation of sections in the human resource division to specifically come up with bicultural or tri-cultural teams that can learn from each other.

References

Barmeyer, C. and Mayrhofer, U. (2008) ‘The contribution of intercultural management to the success of international mergers and acquisitions: An analysis of the EADS group’, International Business Review, 17(1), pp.28-38.

Bird, A. (2013) ‘Comments on the Interview: Cross-Cultural Differences As a Source of Synergy, Learning, and Innovation’, Academy of Management Learning & Education, 12(3), pp.503-505.

Brown, L. (2009) ‘A Failure of Communication on the Cross-Cultural Campus’, Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(4), pp.439-454.

Casserly, M. (2013) Five Signs You’re A ‘Cultural Fit’ For That Hot New Startup (Online) Forbes. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/meghancasserly/2013/03/18/five-signs-youre-a-cultural-fit-for-that-hot-new-startup/?utm_campaign=forbesgoogleplus&utm_source=googleplus&utm_medium=social (Accessed 29 Apr. 2015).

Cheng, S. and Seeger, M. (2012) ‘Cultural Differences and Communication Issues in International Mergers and Acquisitions: A Case Study of BenQ Debacle’, International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(3), pp.116-125.

Child, J., Faulkner, D., Tallman, S. and Child, J. (2005) Cooperative strategy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clerc, P. (1999) Managing the Cultural Issue of Merger and Acquisition. Master. Gasteborg University.

Davies, H., Nutley, S. and Mannion, R. (2000) ‘Organisational culture and quality of health care’, Quality in Health Care, 9(2), pp.111-119.

Dumaine, B. (2014) Renault-Nissan: Can anyone succeed Carlos Ghosn? (Online) Fortune. Available at: http://fortune.com/2014/12/29/renault-nissan-carlos-ghosn/ (Accessed 29 Apr. 2015).

Einhorn, B. and Reinhardt, A. (2005) No One Said Building A Brand Was Easy (Online) Businessweek.com. Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/stories/2005-12-04/no-one-said-building-a-brand-was-easy (Accessed 29 Apr. 2015).

Ernest and Young, (2015) Global hospitality insights Top thoughts for 2015 (Online) EYGM Group Limited. Available at: http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-global-hospitality-insights-2015/$FILE/ey-global-hospitality-insights-2015.pdf (Accessed 28 Apr. 2015).

Ferraro, G. (1998) The cultural dimension of international business. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Froese, F. and Goeritz, L. (2007) Integration Management of Western Acquisitions in Japan. Asian Bus Manage, 6(1), pp.95-114.

Guthrie, D. (2012) Creative Leadership: Trust (Online) Forbes. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/dougguthrie/2012/06/27/creative-leadership-trust/ (Accessed 29 Apr. 2015).

He, R. and Liu, J. (2010) Barriers of Cross Cultural Communication in Multinational Firms: A Case Study of Swedish Company and Its Subsidiary in China. Halmstad: Halmstad University. School of Business and Engineering.

Hill, L. (2013) Job Applicants’ Cultural Fit Can Trump Qualifications (Online) Businessweek.com. Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2013-01-03/job-applicants-cultural-fit-can-trump-qualifications (Accessed 29 Apr. 2015).

Hong, H. (2010) ‘Bicultural Competence and its Impact on Team Effectiveness’, International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 10(1), pp.93-120.

Huang, C. and Sun, V. (2006) BenQs merger miseries: K. Y. Lee eats humble pie.(Online) English.cw.com.tw. Available at: http://english.cw.com.tw/article.do?action=show&id=3254 (Accessed 29 Apr. 2015).

Ji, W. (2012) ‘Cross-cultural Adjustment and Synergy Creation of Foreign Managers in China: An Empirical Study’, IJBM, 8(2).

Kavanamur, D. and Esonu, B. (2011) ‘Culture and strategic alliance management in Papua new guinea’, David Kavanamur and Bernard Esonu, 12(2), pp.114-128.

Kawar, T. (2012) ‘Cross – cultural Differences in Management’, International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(6), pp.105-111.

Lincoln, J. (2009) ‘Strategic Alliances in the Japanese Economy: Types, Critiques, Embeddedness, and Change’, IRLE Working Paper No. 189-09. (Online) Available at: http://www.irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/189-09.pdf (Accessed 28 Apr. 2015).

Mannion, R., Brown, S., Beck, M. and Lunt, N. (2011) ‘Managing cultural diversity in healthcare partnerships: the case of LIFT’, J of Health Org and Mgt, 25(6), pp.645-657.

Ogiermann, E. (2009) ‘Politeness and in-directness across cultures: A comparison of English, German, Polish and Russian requests’, Journal of Politeness Research. Language, Behaviour, Culture, 5(2).

Okoro, E. (2013) ‘International Organizations a nd Operations: An Analysis of Cross – Cultural Communication Effectiveness and Management Orientation’, Journal of Business & Management, 1(1), pp.1-13.

Pitt, M., van Werven, M. and Price, S. (2011) ‘The developing use of strategic alliances in facilities management’, Journal of Retail & Leisure Property, 9(5), pp.380-390.

Prashant, K. and Harbir, S. (2009) ‘Managing Strategic Alliances: What Do We Know Now, and Where Do We Go From Here?’, Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(3), pp.45-62.

Rivera, L. (2012) ‘Hiring as Cultural Matching: The Case of Elite Professional Service Firms’, American Sociological Review, 77(6), pp.999-1022.

Salleh, L. (2005). High/low context communication: The malaysian malay style. In: Association for Business Communication Annual Convention. Ohio: Association for Business Communication.

Samovar, L. and Porter, R. (1994) Intercultural communication. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth.

Van Marrewijk, A. (2004). The management of strategic alliances: cultural resistance. Comparing the cases of a Dutch telecom operator in the Netherlands Antilles and Indonesia. Culture and Organization, 10(4), pp.303-314.

Wang, J. (2009) ‘A Cross-cultural Study of Daily Communication between Chinese and American– From the Perspective of High Context and Low Context’, ASS, 4(10).

Williams, P. (2012) Collaboration in public policy and practice. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Woodsworth, A. and Penniman, W. (2013) Mergers and alliances. London: Emerald Group Publishing.

WSJ, (2015) Cross-Cultural Management Strategy (Online) Available at: http://www.wsj.com/video/cross-cultural-management-strategy/B955CFB2-8AC7-4AFF-BA8C-CC41514D259B.html (Accessed 29 Apr. 2015).

![[Solved] ENGL147N - Week 7 Assignment- Final Draft of the Argument Research Paper](https://prolifictutors.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Solved-ENGL147N-Week-7-Assignment-Final-Draft-of-the-Argument-Research-Paper--240x142.png)

![[Solution] - NR305 - Week 3 Discussion: Debriefing of the Week 2 iHuman Wellness Assignment (Graded](https://prolifictutors.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Best-Answer-NR305-Week-3-Discussion-Debriefing-of-the-Week-2-iHuman-Wellness-Assignment-Graded--240x142.png)

![[Best Answer] NR305 - Week 2 Discussion: Reflection on the Nurse’s Role in Health Assessment (Graded)](https://prolifictutors.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Best-Answer-NR305-Week-2-Discussion-Reflection-on-the-Nurses-Role-in-Health-Assessment-Graded-240x142.png)

![[Best Answer] NR305 - Week 2 Assignment: Wellness Assessment: Luciana Gonzalez (iHuman) (Graded)](https://prolifictutors.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Best-Answer-NR305-Week-2-Assignment-Wellness-Assessment-Luciana-Gonzalez-iHuman-Graded--240x142.png)