Analysis of cultural differences in business negotiation in the garment trade between the UK and China

January 15, 2022 2022-01-15 18:41Analysis of cultural differences in business negotiation in the garment trade between the UK and China

Analysis of cultural differences in business negotiation in the garment trade between the UK and China

Need a dissertation like this one? Get in touch via the email address or order form on our homepage.

Abstract

The present research was carried out with the aim of studying the influence of cultural difference on the business negotiation in the garment trade between the UK and China. There were four specific objectives for the research. To understand the influences of the diverse national values on business negotiation by reviewing and discussing previous research; to investigate how national cultural difference between UK and China affects the business negotiation of Chinese garment companies during trading in UK market; to analyse how the effectiveness of cross-cultural communication may influence the processes of business negotiation between China and UK companies, and to recommend ways of improving Chinese companies’ negotiation cross cultures. The research reviewed a plethora of secondary sources to inform its design and analysis, and it was found that national values, cross-cultural communication effectiveness, and national cultural differences greatly affected the business negotiation processes between these two given countries. The study adopted a qualitative study technique, with interviews as the preferred data collection method. Six managers from three different companies were interviewed and the findings were analysed using content analysis method. From the analysis, it was found that managers felt strongly that communication, national values, and cultural differences were indispensable in the quest for a successful international business deal between any two countries. As such, managers are advised to take precaution in their managerial decisions and ensure that their employees as well as the rest of the management team consider these issues as essential issues in international business management.

Chapter 1 – Introduction

1.1 Background of the research

The contemporary businesses are driven by the heightened need to gain and sustain competitive advantages in an integrated business environment contested with increasing competition, globalization, advancement in technology, and changing management practices (Steers, Sánchez-Runde, and Nardon, 2010). These business influential forces push numerous companies to consider seeking success outside the confinement of domestic or familiar business environment. Fundamentally, Steers, Sánchez-Runde, and Nardon (2010) identify that businesses experience a burgeoning number of transactions characterized by their involvement with international customers, joint ventures, and supplier relationships. To meet business objectives in the more integrated business world, communication at an international level is paramount. Arguably, Huang (2010) posits that a company’s profitability would in part be influenced by its success in business communications strategies and skills, including negotiation skills. As such, cross cultural communications and more specifically, negotiations are inevitable in the daily business transactions.

Negotiations, from a broader perspective are described as all systems of communication, discussions, exchanging of opinions, consultations, and attainment of a formal agreement (Chang, 2006). Literatures identify that there are two types of negotiations: transactional, which relates to the product purchasing and selling, or conflict related negotiations. According to Fox (1994) findings, before pursuing negotiations, parties involved should begin with preparation, which encompasses market surveys, perhaps for the product prices, understanding of the motivations, values and beliefs of the other party. In affirmation, preparation leads to attainment of significant knowledge that offers suitable bargaining powers, which could provide leverage during negotiations.

Chang (2006) identifies that while some researchers are adamant that negotiation behaviour occurs in a predetermined background where cultural backgrounds of the negotiators are irrelevant, others posits that negotiations are fundamentally dissimilar in different countries and take unique forms from country to country. Even so, Seng and Lim (2004) cautions that business negotiations in cross-cultural frameworks is not concerned with achieving a consensus or exploiting a company’s position, but maintaining undue respect for the values (culture) of the negotiating partner and forming continuing amiable business relationships. To underscore the significance of respecting different culture in the field of international negotiations, a great level of sophistication has been recorded in the way organisations approach negotiations internationally (Montana and Charnov, 2008). As such, borrowing from earlier research, whose findings are resonate in the more contemporary research, gaining insights into different cultural norms, values, and beliefs is paramount to prospecting successful negotiations at a global level (Cricillo, Fremantle, and Hamburg, 2000).

With the proliferation of international garment markets, business executives have increasingly gained knowledge and cognizance of the significance of cross-cultural communication in influencing business success and offering valued competitive advantages (Huang, 2010). However, some top managers in international garment trade sometimes fail to recognise the importance understanding various barriers brought about by cultural differences. Given the common understanding that culture generally varies from one to the other (Huang, 2010), cultural differences are more than likely to influence company decisions such as, modes and strategies of entry in to international markets, decisions to target various markets in foreign environments, decisions to formulate marketing programs, as well as, the power to control operations in foreign markets. Successful negotiations are vital in securing good business deals.

To various extents, diversity in cultural backgrounds culminates into different forms of negotiations. Tse, Francis, and Walls, (1994) found that individuals from diverse cultures utilize significantly unlike negotiation methods. Such negotiation approaches may take the form of communication styles, persuasion strategies, and etiquettes used. Nevertheless, Liu (1996) argues that this relationship is not absolute, but managers involved in negotiations should avoid stereotyping at all costs. Propagating stereotypes leads to distrust between the parties involved in negotiations, not to mention, creation of obstacles that negatively influence the parties such as misunderstandings (Bolewski, 2008).

In order to comprehend the influence of cross-cultural difference on the business negotiation, cross-cultural studies delineating communications models and theories can appropriately be applied. On the one hand, various national culture models such as Hofstede five dimensions of culture provide suitable contributions to understanding the strengths and weaknesses of different cultures nationally. Moreover understanding why business negotiations fail across culture would lean towards the explanations offered, for instance, by Hofstede five factors, including power distance, masculinity, individualism, long-term orientation, and Uncertainty avoidance index (Hofstede, 2011). Other considerations as articulated in earlier contributions in the field of cross-culture and negotiations include business etiquette, language adeptness, and history (Martin and Larsen, 1999). Generally, as Martin and Larsen (1999) identified, misunderstanding results in communication process failures, whereby, language obstacles are the common contributors.

On the other hand, Edward Hall’s high and low context culture theory is essential in describing the cultural dimensions upon which the research can draw understanding of the cultural factors that influence decision making and negotiation behaviour across cultures. Without disregarding the verbal and nonverbal codes of communication, communication between people from different cultures is affected by the context in which interactants meet. Hall and Hall (1990) asserted that salient features of the context include the physical, perceptual and sociorelational backgrounds, as well as the cultural backgrounds. Salient connections with the Hofstede five-dimension model are observed in the consideration that the cultural context entails features as collectivism and individualism. Based upon Hall’s descriptions, physical environment entails the definite geographical setting, for example, office while perceptual arena describes the attitudes, impetuses, and intellectual temperaments of the interactants. However, the relationship between parties in a negotiation such as, the superior/subordinate relations is relevant sociorelational consideration. Of great importance is that the extent to which parties concentrates on the above contexts while negotiating differs substantially from culture to culture (Hall, 1976).

From a different research, Peleckis (2013) in his study identified that the context of negotiations at the global level is contested with differences between several cultures. The research centred on Hofstede’s five dimensions of culture but included other relevant factors as follows: context factors, communication such as expressive (emotional) dissimilarities between the negotiating parties, a continuing attitude towards communication.

1.2 Research rationale

From a theoretical perspective, this research aims to help in adding to the body of knowledge regarding the influences of cultural difference on business negotiations. Previous research has focused on discussing the dimensions of cultural dimensions in businesses across cultures with very little explanations to offer understanding of cultural intelligence and it influences on business negotiations across cultures. As such, this research is relevant and much needed in the current times where globalization is the order of the day.

The consideration of investments in international markets entails preparations in terms of researching for increased knowledge regarding the traditions, variations, and properties that define the prospect global market. In order to facilitate business processes, international businesses seek to amend their operations or practices to fit the particularities of the other party in a partnership, strategic alliance, or joint venture (Peleckis, 2013). This research comes in to assist businesses achieve this objective through the analysis of cultural dimensions with the aim of providing knowledge regarding the incompatibilities of different nations chiefly through the Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Moreover, international companies will benefit in their conceptualization of global business negotiation processes, given the articulation of different cultural dimensions. The importance of understanding cross-cultural communication with a bias on negotiation is prominent more so due to the possible risks that would befall an international company with poor negotiation skills. Important to note is that a distortion in cross-cultural communication has a high probability of weakening a company’s competitive position in the international arena thereby hindering it from achieving business objectives and eventually leading to company demise (Steers, Sánchez-Runde, and Nardon, 2010).

Moreover, this research emerges as a significant endeavour that should lead to increased understanding of the different cultural communication hindrances to effective business negotiations. Some of these hindrances may include, etiquette (greeting, eye contact), attitudes towards time, negotiation styles (which may be as an influence of culture, for example, ideologies, gift offering customs, and importance of gestures among other factors (Montana and Charnov, 2008).

The need to understand cultural difference that guide effective operations in international markets is exemplified through some highly popular blunders by international company managers depicting disregard for culture differences. It is therefore significantly imperative that this study seeks to offer the conceptual understanding upon culture intelligence (learning about culture in terms of diversified histories, values, beliefs, and local value for time and responsibilities) can be based. Greater extents of understanding and engagement in communications between the negotiating parties and with respect to cultural value and beliefs of both parties increase the chances of positive outcome of the negotiations.

1.3 Research aim and objectives

This research aims to study the impact of cultural difference on international business negotiation and how it can increase the rate of negotiation success by interviewing three different Garment Company including Bosideng and Dayang Group and Youngor Group from China which are doing garment business with different countries including the UK. To achieve this aim, the research is guided by the following research objectives

- To understanding the influences of the diverse national values on business negotiation by reviewing and discussing previous research

- To investigate how national cultural difference between UK and China affects the business negotiation of Chinese garment companies during trading in UK market;

- To analyse how the effectiveness of cross-cultural communication may influence the processes of business negotiation between China and UK companies

- To recommend ways of improving Chinese companies’ negotiation cross cultures.

1.4 Research questions

Based on the above research aim and objectives, this research will seek to answer various questions regarding cultural intelligence and its relevance in influencing business negotiations. The following are the questions

- How do culture and values differ in the UK and China?

- What are the relevant and most significant considerations for successful business negotiations from a basis of cultural values and beliefs in the UK and China?

- How to strengthen cross-cultural communication during business negotiation of the UK and China garment companies

1.5 Research outline

In order to achieve the research objective set earlier, this research includes seven chapters. From the start, the research introduces the concepts of negotiations and cross-cultural differences. This is done through the research background that provides relationship between the cross-cultural difference and business negotiations from the existing theoretical basis. Other relevant parts of the first chapter include, the research rationale describing the significance of the research in the modern day business arena, and the research aim and objectives that provide guidance for this research. Secondly, the research discourses the earlier and more modern literatures with a bias on seeking relevant information from credible sources including peer reviewed journals, books and internets sources of cross cultural differences and negotiations. This chapter will focus on discussions of the cross-cultural communication, national cultural difference, cross-cultural negotiation theory, the influence of national cultural difference on business negotiation, and the improvement of cross-cultural communication competence.

Thirdly, pertinent methodological methods used in the research, as well as the reasons for their choices will be discussed in the third chapter. In the fourth chapter, the research will make the data analysis and get effective research findings. Moreover, the fifth chapter will entail relevant discussions of the research findings. The sixth chapter comes to the final conclusion and put forward recommendations based on the findings. Besides, it also shows research limitations and how future research will be guided. The last chapter is personal reflection.

Chapter 2 – Literature review

2.1 Introduction

Basing on the objectives and perspectives of this research’s theoretical and empirical arms in the quest to better analyse the influences of cross-cultural difference on business negotiation, this chapter will entail past papers that have been done and consider relevant models shade light to different viewpoints taken in regards to the topic. To achieve these credible sources including relevant internet sources, books and past scholarly journals will be considered to give a well analysed review. To better understand the topic under review, theories that are hinged on cross-cultural difference in relation international business front and how they affect business globally will discussed using Hofstede framework and context theory. To add on, this paper will analyse models that affect the cross-cultural engagements and communication from an aspect of language misunderstanding (Hofstede et al., 2002), and pertinent issues of non-language communication conflicts for instance; customs, etiquette, silence, eye contact just to name a few (Liu, 2009). Additionally, cultural diversity that is brought about by national cultural differences and negotiation platforms form a basis of understanding better how the global business community crosses paths to making successes and the flaws that befall internationalisation in the business initiation processes (Pagano, 2007).

2.2 Cross-cultural negotiation theory

Negotiation is one of the most critical elements in any business interaction (Brett, 2001). In fact negotiation can be described as the process in which a number of parties get together to discuss and evaluate common and conflicting interests. The main aim of such a seating is in the hope that they will reach a common agreement which in turn will benefit both sides (Crump, 2011). The negotiation process in the business realm is generally a very complex process, which is easily influenced by the diverse cultures from which the parties have been socialized, educated or even reinforced (Lee et al, 2011). A good example can be given by the fact that any person’s conduct at a time of negotiation will be determined by their ethnic encounter which is embedded too deep in the cultural background. As a result, behaviour negotiations are normally consistent within cultural boundaries making each culture to have its own distinct negotiation style (Ready and Tessema, 2011).

On this note, when the negotiation involves international business perspectives then it is referred to as inter-cultural or cross-cultural negotiation behaviours (Crump, 2011). At this point, the parties involved come from different countries and do not share the same cultural thinking, feeling or even behaviour (Lombardo, 2009). Such aspects can in turn easily affect the entire negotiation process and its subsequent outcome. However, it’s very crucial to ensure that mutually beneficial outcomes are achieved from cross-cultural negotiations hence the need of using an elaborate and all inclusive negotiation process as outlined in the discussion that follows (Ready and Tessema, 2011).

The negotiation process that normally precedes a cross-cultural business negotiation can easily be divided into two stages: the non task related interaction and the task related interaction (Lee et al, 2011). The non task related interaction will outline the whole process of the members engaging in the negotiation getting to know each other very well (Lewicki et al, 2015). This phase involve the actual face to face meetings whereby the actual business aspects are left out of the meeting. The outcome of such non task related meetings is normally influenced by perspectives such as the distinction of status, formation of impression and the level of interpersonal attraction achieved between the negotiators (Bhagat et al, 2012).

The second phase or stage of negotiation process will involve the actual interaction of the business agreement (Rodrigues, 2009). It normally involves the sharing of the needs, tastes and preferences of the negotiators regarding the business aspect on the table. This stage takes a keen interest on the exchange of information, persuading and bargaining strategies, and finally any making of concessions, which at the end results into the final business agreement (Sycara et al, 2013). Once the agreement has been done, the parties engage in the signage of a contract which legally binds the negotiators to own their distinct side of the agreement (Fells, 2010). This then marks the end of the negotiation process.

Negotiation in the international business front

Negotiation in relation to international business coffers can be described as an agreed interaction of a business nature that involves parties of different nationalities coming from different cultural backgrounds (Liu, 2009). This process is primarily aimed at making a mutual understanding in redefining the mode of associations and interdependencies which will form the need to necessitate the business partnership (Lee, Adair and Seo, 2011). Following the diversity of international cultures, the success of international trade is determined by the skills involved in negotiation amongst the potential trading partners (Groves, Feyerherm and Gu, 2014). This forms a prime interdependence that this paper focuses to unlock the potential and the systems that can aide its success or fail.

2.3 The influence of national cultural difference on cross-cultural business negotiation

2.3.1 National cultural difference

National culture can easily be defined as the values, behaviours, beliefs and norms which are a main characteristic of a certain national group (Dowling, Festing and Engle, 2008). Such forces normally tend to be very distinct in the country’s culture, an aspect which in turn impacts the legal, educational, political, technological and socio-cultural frameworks adopted in the country (Hofstede, 1991). Such are the ones which demarcate and make one country’s culture to be very different from the culture of another nation, hence resulting to national culture differences (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). In relation to this, it is fair to state that national culture will therefore provide a big context for business negotiations since it takes place within the confinements of cultural institutions which are governed by the norms and values (Minkov et al, 2012).

National culture highly affects the business negotiation processes and subsequent outcome, making these practices differ from country to country. The national culture in fact will deliver on the negotiation style which the cultural diverse business partners will use during the negotiating process (Leung et al, 2005). It will also define the way these people will perceive or even approach the entire process as they will tend to view issues like power, time, risk, flow of communication or any complexity differently, and as based on their cultural background (Chen, 2006). A good example can be shown by the fact that individualist business negotiators will always tend to be coercive or aggressive during the negotiation process. On the other hand, collectivist business negotiators will be more inclined towards the formulation of solid relationships from the entire process. All these aspects are generally strongly embedded in the national culture which these people come from.

2.3.2 Hofstede’s cultural framework and impact on cross-cultural business negotiations

Hofstede model is the model that had generally look at many of the aspect in cultural problem and also balance the weight of each dimension to create a better view to the whole problem of cultural. Hofstede model of cultural dimension divided into six dimensions which each of them are used to describe and research on different aspect in culture (Hofstede, 2005). The model was widely used by many researchers to explain the effect in business and also communication. Hofstede model of culture dimension is explain by researcher Hofstede & Minkov (2010) as a model which had set up a s a framework to explain in detail about culture dimension which can use to describes the effects of a society’s culture on the values of its members, and how these values relate to behavior, using a structure derived from factor analysis. Hofstede’s cultural framework will be used in this dissertation which is in Appendix 1. The six Dimension will include the Power distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, Masculine/ Feminine, Individualistic/ Collectivistic, Time Perspective and indulgence/ restraint. The six dimensions will be a very good example that cultural intelligent in six of this dimension can help business to increase success rate in business negotiation (Wittenkamp, 2014).

The five cultural dimensions as supported by Hofstede has shade so much light in the comparative study of the differences in national cultures as perceived by difference countries. They will be analysed in the light of exactly how they affect business negotiation process in regard to the objectives, ways, time and place arrangement, etiquette, communication style, contract agreement of negotiation. The first dimension is the power distance dimension which will have a direct impact on the communication style and etiquette which is used during the negotiation process. Sears & Jacko (2007) researcher in human interaction will explain the term of power distance as the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations and institutions (like the family) accept and expect that power is distributed unequally.” Cultures that endorse low power distance expect and accept power relations that are more consultative or democratic. The organization with less power distance will having more interaction between employee and manager which eventually will be one of the core that will effect negotiation. This is so since the communication style in many cultures is determined by power distribution in the institutions (Hofstede, 1991). In countries with high power distance the negotiators will tend to value the communication style will always tend to be direct and to the point, and the negotiation way to be very formal and adhering to a strict protocol (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). In low power distance countries, the negotiation ways will tend to be very respectful, while the communication style dominated with a lot of softness and non-verbal language like gestures (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005).

Uncertainty avoidance is the second core of culture intelligent which can affect the international level business negotiation. Uncertainty avoidance is the measures if people are comfortable with taking risks, ready to change the way they work or live (low UA) or if people prefer the known systems (high UA). Sears & Jacko (2007) explain the term as reflects the extent to which members of a society attempt to cope with anxiety by minimizing uncertainty. People in cultures with high uncertainty avoidance tend to be more emotional. They try to minimize the occurrence of unknown and unusual circumstances and to proceed with careful changes step by step planning and by implementing rules, laws and regulations. In contrast, low uncertainty avoidance cultures accept and feel comfortable in unstructured situations or changeable environments and try to have as few rules as possible.

The will have a direct impact on the level of risk the negotiators can take, thus impacting on the objectives and contract agreement perspectives of the process. Therefore, business negotiators from national cultures with high uncertainty avoidance will always tend to want to safeguard the future sustainability of the business objectives by pushing for the signing of a contract during the business negotiation process, while those coming from low uncertainty avoidance cultures will be more keen on developing long-term relationships as their level of trust is high and fear for unfamiliar situation low (Minkov et al, 2012). It is very obvious that when a business is going to cooperate with other business to run a program or a business, it is very important to know how much risk will the partner is willing to take as dragging a business into risk will cause business negotiation to fail. Ubobong (2014) in the previous chapter had describe uncertainty avoidance is the first cultural intelligent that must be process in international business. The same result had been found in Zieba (2009) research in cross culture negotiation which Zieba state that there is always risk involved in negotiations. The final outcome is unknown when the negotiations commence. The more creative one of the side is the more risk will it drag the partner of negotiation into and increase the chance of failure in negotiation. Beside that the major problem that will exist when dragging partner into risk is partner will start to question on why should they believe the first party and take on the risk. Both of the researcher had strengthen the possibility of the statement which cultural intelligent in uncertainty avoidance can be helpful in increasing the possible of succession rate in business negotiation in international level business.

The third dimension is the individualism against collectivism perspective. There are people with different set of working culture which some of them prefer to work alone and some of them will like to work in group and believe group can increase effectiveness. In individualistic societies, the stress is put on personal achievements and individual rights. People are expected to stand up for themselves and their immediate family, and to choose their own affiliations. In contrast, in collectivist societies, individuals act predominantly as members of a lifelong and cohesive group or organization. (Sears & Jacko, 2007). This dimension will play a big role in affecting the time and place aspect of the negotiation process. In individualistic cultures the people will tend to be very task-oriented thus choosing very formal places like in-house meeting or board rooms whereby less time can be used in the closing of the negotiations (Peterson, 2007). In collectivists cultures the meetings can be held in informal venues like hotels whereby sufficient time will be used in learning the business partners before the negotiation process is completed, as they are normally relation-ship oriented (Hofstede and Fink, 2007). Besides as research Hofstede, Jonker and Verwaart (2008) had carry on a research of individualistic/ collectivistic in trade state that people with individualistic culture would prefer to cooperate in smaller group when and share the achievement with smaller group of people while in the other hand collectivistic would prefer to make the achievement bigger and share in many.

The third core of culture intelligent which can help business to increases in succession rate in negotiation if negotiator know more about it. Masculine societies have different rules for men and women, less so in feminine cultures. Masculine societies have different rules for men and women, less so in feminine cultures. Sears & Jacko (2007) explain that in masculine cultures, the differences between gender roles are more dramatic and less fluid than in feminine cultures where men and women have the same values emphasizing modesty and caring. The method seem to be not a very big deal in international level business negotiation while Forbes researcher Kirdahy (2008) had make a research and end up with conclusion that men and woman can equally run on the field of business. The assumption also included in business negotiation that woman can be no different than man in business negotiation. However there are actually different set of rule run in masculine societies for man and woman where any break of the rule may be treat as unrespect and cause immediate terminate of business negotiation. The report of Beyer (2001) the reporter of Time Newspaper had state the issues that Muslim country woman cannot be the same as other country where in some country such as in Malaysia man cannot be too close to woman or not it will be counted as molest in sharia law and will cause misunderstanding in both party. In this situation it is hard to denied the importance of Masculine/ Feminine cultural intelligent in international business negotiation.

Beside that it is also very important for a party in negotiation to use the right gender to negotiate in other country. As some of the country hold the culture where they dislike woman to be the representative in negotiation where they will take the action as disrespect in business which will cause the negotiation come out to be negative. One of the example had been made by Alexis & Antoine (2014) in their research on Hofstede in Japan had given the conclusion that feminine societies are more likely to stress on life quality and intuition at the work place than masculine societies. . They state that Japan is a masculine country where it’s very hard for a woman to reach high levels in companies. They also do not prefer woman to be in negotiation which they will likely to treat it as disrespect. So Masculine/ Feminine is also an intelligence which business need to process to gain better outcome in business negotiation. Besides, in cultures dominated with masculinity the communication style during the negotiation process will be very independent and assertive in nature even while arriving at the decision, while in feminist cultures it will group oriented in nature and have decisions arrived through a consensus (Hofstede, 2011).

Lastly, long-term against short term orientation delivers the fourth dimension of this framework. This dimension will also affect the contact agreement perspective of the negotiation, as cultures with short-term orientation will allow strict rules to be followed thus ensure that contracts have been signed during the negotiation process, while long-term oriented cultures will tend to be more relaxed and engaging to form solid relationships during the process (Hofstede and Fink, 2007). The fifth core of culture different that will affect business negotiation is the time perspective in Hofstede model. Time perspective is how a business will intend to time can often be a stumbling block for Western-cultured organizations entering the China market. The length of time it takes to get business deals done in China can be two or three times that of the West. On many occasions, the initial deal takes the longest, allowing the Chinese client to feel that a suitable “courtship,” upon which a mutually beneficial and sustainable relationship can be built. So if a business negotiate initial meeting with a Chinese company does not yield an immediate sale, they do not despair. As time is the Chinese’s greatest ally (Kriss, 2006). This is because most of the business in different country will treat time differently. Example in some country they will like to invest in long term business rather than short term business as they believe long term business can bring more profile to the company in the future. As a long term business and a short term business meet in a negotiation, usually they will not end up with a successful result of negotiation.

2.3.3 Edward Hall (high and low context culture theory) and impact on cross-cultural business negotiations

Hall (1976) illustrated that a very critical dimension aspect of the negotiation process is based on the communication context involved during the process. Furthermore, the same source when ahead to claim that national culture falls in the high to low context when highlighted in relation to communication perspective (Hong, 2013). In low context cultures, the kind of communication used during this process is normally very explicit in nature (Wang, 2009). The communication is normally very formal and mainly verbal in nature. In the high context cultures on the other hand, the communication tends to be relatively less verbal and include other non-verbal expressions like gestures, body language and facial expressions (Westbrook, 2014). Therefore, Hall (1976) further affirms that it is very difficult for one to get into a business negotiation process with high context cultures unless they are completely ‘contexted’, since they will not make sense out of the communication.

2.4 The influence of the difference of national values on business negotiation

According to Lee et al., (2006), interpersonal relationship is defined as a powerful or deep link between two or more individuals that may vary in duration from enduring to brief. Different nations have different interpersonal relationship orientation. In China, for instance, this personal connection is referred to as guanxi (Gold et al., 2002). Chinese and Indian citizens’ places high premium on individual’s social capital within their relatives and friends and close confidants while for Americans, there is a belief in networking, institutions and information (Lustig et al., 2006). Although globalisation is making guanxi to be an out of date value in China, it still affects most business negotiations. Lee et al., (2006), points that in China during negotiation, the man with the most gunaxi wins. In Chinese culture, the gunaxi system advocates a strict reciprocity style where if a friend did you a favour today, the favour must be returned. The Chinese call it “Hui Bao.” However, the reciprocity does not need to be immediate. The national culture of America stresses on immediate reciprocity where if one makes concession in the morning during negotiation, in the afternoon he expects the concession to be returned to him (Brantlinger, 2013).

Besides, traditional value of a country also influences peoples’ behaviours within it. For example, the central principle of the Confucianism theory is harmony, proper behaviour through duty and loyalty and respect, which influences Asian nations especially China as an influential value. According to Warner (2010), Confucian is a hierarchical relationship. These values are expected to be showed to a leader by his subjects (Cheng, 2004). To put it plain the theory advocates for every individual to be cognizance of his/her place in the society. It gives seniors the benevolence duty over juniors and juniors according to the Confucian theory owe seniors reverence (Cheng, 2004). In this vein, when negotiating more especially with the Chinese, it is not difficult to not the influence the Confucian ideas has on negotiations. The Confucian model has been added to Hofstede (1991)’s four models of cross-cultural communication to differentiate western cultures from Chinese cultures (Rhodes et al., 2005). According to Cheng (2004), the theory of Confucianism and Taoism stresses on patience and survival instincts this affects negotiations involving the East Asians and American since who are individualistic and value time. Negotiations between these two cultures are quite challenging since the Confucian ideas stress on following protocols that democratic nations see as a waste of time.

Furthermore, there is a scanty body of evidence about how business negotiations get affect by religious beliefs (Chang 2003). The study conducted by Tu and Chi (2011) about religious beliefs in three countries China, Taiwan and Hong Kong illustrated that religious of the negotiators influences negotiations to a greater extent. After comparing the negotiating styles of these three nations, Tu and Chi (2011) concluded that region had soaked people from these nations with particular values and attitudes consequently the negotiations in this three countries varies sharply. In the same year, Daneefard and Farazmand (2011) set up a study to investigate the negotiating styles among three nations U.S, Taiwanese and Iranians. There results confirmed Tu and Chi (2011) investigations. Their results revealed that negotiation styles in these three countries vary to a greater extent depending on the religious beliefs of each nation. It is therefore of the essence of business practice to be knowledgeable in terms of communication more importantly during business negotiations. Chang (2003) recent study of the Chinese society indicated that knowledge about the religion of the parties at the negotiating table increases the likelihood of successful deals. Finally, Thompson (2005) suggestions still carries a strong message as it were 13years ago. To him business negotiations should present a win-win situation where a deal struck by the parties at the negotiations covers virtual interests from both sides.

2.5 The influence of the different communication manner caused by national culture and values on business negotiation

2.5.1 Cross cultural communication in business negotiation

Greenfield (2013) argues that cross-cultural communication can be termed as a mode in which the international business finds its way to exchange and use modes of communication to convey messages and information for the sake of enhancing the business itself. Peterson (2004) acknowledges that the cultures are rich in modes of communication and it’s through this intelligence that the international business front is developed. This analogy is supported by Zhu (2008) who points out that the culture of yesteryears has evolved to embrace globalisation and the transformation is remarkably leading the world into homogeneous business platform. On the other hand, cross-cultural communication according to Lombardo (2015) is key to business success for an organisation that has a workforce of divergent origins. This will form a divergent but rich way of working with different cultural backgrounds and experiences.

However some scholars have come to the critic that this arrangement may pose some threats especially when language barrier and values differ in the same organisation (Elsaid, 2012). For instance, the research posed clear implications that were noticed in the pharmaceutical companies in Egypt having workers of the Egyptian origin and some technicians from the US. Cultural and religious believes counted one of the highest discrepancies according to the research. On the other hand international business front and negotiation may be hampered on the same grounds (Neves and Melé, 2013). To curb the misfortunes that come with such discrepancies, there are several theories and models that can be used to help shape fair negotiation to enhance global trade (Kankaras, 2009).

2.5.2 Cross cultural communication models

To aide a successful communication through a multi-cultural front for the sake of internationalization and business development, players in the industry have adopted several models and theories to break risks that hinder effective global business success (Merkin, 2011). On that note, scholars and business gurus Konya (2006), Dawkins (2006) and Hernandez and Kose (2011) have been analyzing different ways to reduce the hindrances like language, cultural value differences and norms, religious differences among others to a bearable level to effectively initiate and develop businesses across the borders.

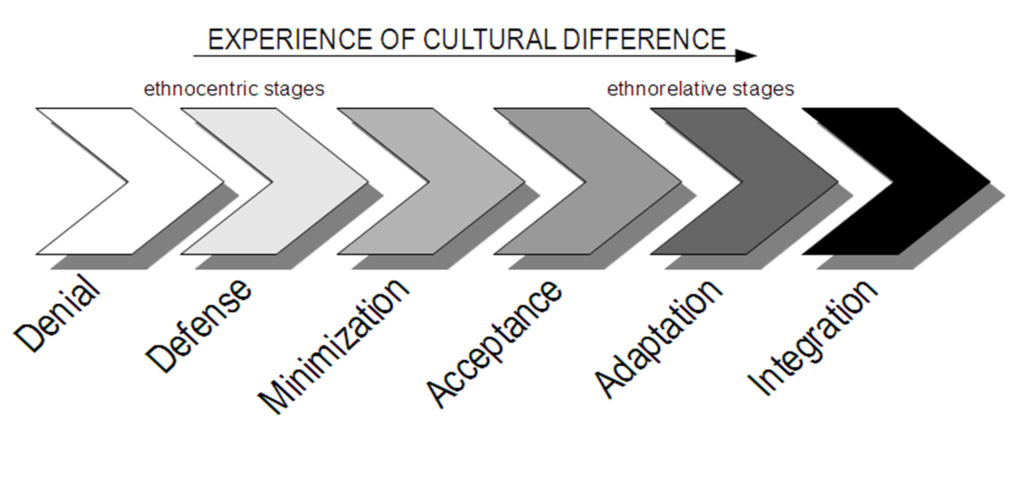

Developmental Model of Inter-cultural Sensitivity (DMIS)

According to this model, Hernandez and Kose (2011) points out that in developing intellectual competence that will form a breakthrough in solving risks of international business. Therefore, business partners ought to channel the growth through six major stages of growth with each stage characterised with different viewpoints approaches as shown in figure 1 below (Communicaid, 2015).

Fig. 1. Developmental Model of inter-cultural sensitivity (Bennett, 1993)

The first part called ethnocentric stages that entail the denial, defence and minimisation denotes the times individuals tend to reject engaging with other unfamiliar cultures (Hewer and Roberts, 2012). In addition, the look is subjective viewing others from a superior context whereas, the acceptance adaptation and integration forms what Jin (2012) terms the ethnorelative stages accounts for parties beginning to acknowledge other cultures and may tend to have some curiosity to learn about them. The parties change into accepting and ingest the new cultures with optimistic perceptions (Hewer and Roberts, 2012). In aiding negotiation, its therefore important that this transition takes place well for the business to thrive. In addition, the stages are primary to transiting from a stranger to understanding the other partner from a cultural perspective before engaging in business. Cross-cultural perspective shapes the understanding, perception and possible resultant ways and mode of negotiation best suited for that culture (Ibarra et al., 2001).

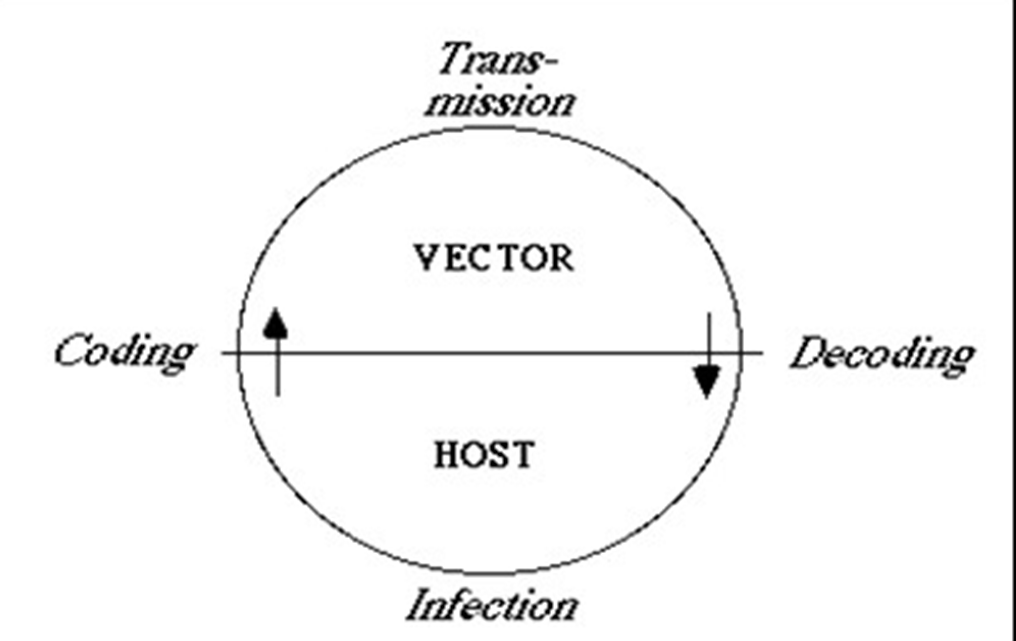

Memetic theory the theory of Memetics

This theory critically evaluates cultural values as having attachments to their hosts in that each culture has a way it manifests itself in the believes and values of an individual (Dawkins, 2006). Scholars have studied this tendency and alluded that just like genes are passed through generations, memes according to Aunger (2000) is a transferable unit of the culture that is handed on from one person to the other. Ding (2014) supports the theory in his research that, associates the adaptation of cultural diversity to instilled memes in people. These memes vary from one culture to the other and that is why they form a critical evaluating point in considering international business through a diverse background of memes (Rickards et al., 2008). Juming (2009) elaborates how the memetics theory has transformed the Chinese business models from traditionalist business in the western provinces with a wave of capitalist eastern provinces that were dominating with adopted western world-kind of life. This factor was earlier synthesised by Carney and Williams (1997) as a compound approach onto which international trade rides on. Additionally, Tracy (2013) portends that association that forms globalisation needs understanding of the parties involved and their cultures. This forms the way they carry out their business and their negotiating mannerisms. Ibarra et al. (2001) say that negotiation is strongly hinged in the cultural values and believes that forms the association and models business negotiation rely on as shown in the figure 2 below.

Fig 2. Lifecycle of memetics and culture (Velikovsky, 2012).

2.5.3 The influence of the manner of cross-cultural communication on business negotiation

Cross-cultural communication can be done in two distinct ways; the language misunderstanding and the non-language communication conflicts like, etiquette, custom issues, actions, voice, time, silence eye contact among others.

Language misunderstanding

Language is the basic manner in which the communication amongst the trade partners will pass the information and the agreements if reached in a business agreement (Lo Bianco, 2005). This means that, language becomes an integral medium of effecting this communication (Morita, 2014). Consequently, with different languages throughout the world business partners and associates should find a way to break this barrier for effective understanding. In the international business front, language barrier is a common impediment with different cultures having different languages (Musolff, 2014). Conversely, Crowcroft (2012) advocates that, in attaining a good negotiated business understanding, countries ought to find ways to take business beyond the cultural front through formulating internationally binding mechanisms to initiate understanding. In absence of that, language misunderstandings dominate following varying backgrounds, thus message is not relayed well. For instance a native Chinese business person will find it hard to trade with a Mexican counterpart on the basis of language barrier. However, as several literatures have put it, internationally recognised languages blend in well with use of translators (when needed) to shape the trade agreements (Fantini, 2001). This also has facilitated learning of commonly recognised international languages to help the rapidly increasing global trade (Lo Bianco, 2005).

Non-language communication conflicts

Several non-language communication conflicts come to play in relation to cultural backgrounds with different perceptions in the globalization and the notions taken with different bodily expressions and other acquired attributes (Tessema and Ready, 2009). Etiquette that involves the dress codes and physical presentation for instance greeting and respect portrayed to fellow business partner is vital. For instance Singapore and many East Asian countries have a tendency of bowing with hands held together as a form of recognition, greeting and respect, a thing that is non-existent in the west where they prefer a handshake (Stromquist, 2014). Such clearly different mannerisms are culturally embedded and determine the way one will close their business agreement. Eye contact is another vital non communication attribute that may make or break a business deal. For instance a person cultured to keep direct eye contact in UK as a mode of exuding confidence and sobriety may be taken as a mode of uncultured norm on the gulf states more especially if it’s a female business associate (Mackiewicz, 2005).

Their influence on cross-cultural business negotiation

According to Griffith (2003) it is a commonly agreeable fact the pivotal role communication plays in international negotiations. Charles (2007) emphasises that for business professionals who work globally and interact daily with clients and professionals from diverse background it is of greater importance to have a grasp of business language that according to Lewis and Gates (2005) is English. Charles (2007) arguments seem to concur with Martin (1999) writings on communication. According to Martin, (1999) limited mastering of negotiation’s language brings misunderstanding and consequently negotiation failure. Martin attributes this difficulty in negotiation of cultural differences. Hofstede (2011) on his part emphasise that communication involving people from different setting more especially on negotiation demands an executive with a keen understanding of cultural diversity.

There is a large body of evidence showing how language can affect business negotiation (Handford, 2010). According to Handford (2010), how language is utilised during negotiations sends strong signals about the person negotiating and the organisation he represents. U.S and Canadians are known to speak directly, stating what they mean and meaning what they say as oppose to Asians (McNamara, 2003). The Asians can consider this culture blunt and rude (Hofstede, 2011). While accepting Harzing and Feely (2008) put it plain that language barrier is just but a tip of the iceberg. He points that various cultures have their own customs for communication more especially in business and social situations and that negotiations generally takes place within a confined period that members may not have the laxity to understand each other well. These are not new ideas as they had been communicated before by Martin (1999) and Hofstede (2011). In situations like that, Harzing and Feely (2008), points that it is difficult to comprehend and explain the choice that a partner from another side of the table is making. Handford (2010) therefore makes his final submission that such situations make it harder for the negotiators to deliver value efficiently due to misunderstanding.

Furthermore, for effective business negotiation, the body of expressions used by the negotiating parties needs to be as clear as possible asserts Plum (2008.). Expression is used here to mean clarity and simplicity in the choice of words more especially during global negotiation involving business executive from different cultural setting and whose first language is not the language of management (English). People who come from cultures that value hierarchy and authority like the Japanese and the Chinese values formal expression during negotiations, while for those western cultures whose values are shaped by democracy uses informal expressions to create friendly link and accelerates negotiations (Lee et at., 2006). In China Plum (2008) continues, informal expression is only allowed in cases where trust and firm relationship has been sealed.

According to Earleyand Mosakowski (2004), the body is a strong communication device. Body parts are used by people around the globe to convey different messages. When someone is anxious, for instance, he may lock his ankle to show it, rubbing hands as also been used by negotiators to show that they are expecting good things, during negotiation, when an individual touches his nose with an index finger this is a sign that he does not like what is being offered. Stress at the negotiating table is shown by clenching a fist (Earleyand and Mosakowski, 2004). While some of the gestures are universal, there are some which are country specific. Americans, for example, uses circle with the thumb and index finger as a symbol of “OK” meaning everything is right. In Brazil, this is a sign of vulgarity; in France, this means “zero” or nothing in Japan the symbol means “money.” While the Chinese show affection by touching a child’s head while this gesture is offensive in Arabic countries.

Differentiated behavioural manner caused by national cultures and values is an important factor that influences business negotiation. Using the time for instance, Wang (2005) believes that American and Europeans in general have view time as unilinear and would, therefore, wish the negotiation be completed very fast for them to do other businesses. To them negotiating activities needs to be scheduled failure to which they get angered. To use Graham and Lam (2003) quote, American and Europeans “budget their time as their money.” They are often restless during negotiations and frequently rush for deals. Graham and Lam (2003) reveals that this behaviour makes them be exploited by the Chinese and Japanese during negotiations. The Chinese behaviours, on the other hand, have been influenced by the Confucian culture. The culture places more value on creating rapport before getting down to business a behaviour considered by Westerners as a waste of time during the negotiation (Cheng, 2004). The Asians negotiation culture is almost similar to that of Russian business executives. Adler and Gundersen (2007) submit that Russians in sharp contrast with the US view time as the cheapest commodity that is an inexhaustible resource. The Russians negotiations skills are influenced by dilatory model and bureaucratic. Businessmen from Russia often do not rush into making deals only if they are in urgent need of what is offered.

2.6 The improvement of cross-cultural communication competence in business negotiation

International executives who are expected to be sharp in cross-cultural communication competence frequently use their meaning to conjure sense of someone else’s reality. These foreign executives as Quappe and Cantatore (2007) submits lacks cultural competency of their own behavioural rules that can assist them adequately understand others during business negotiations. Kim and Gudykunst (2003) acknowledge that meaning is hard to be transmitted in an ordinary communication between two or more people chiefly because of ambiguity in the language spoken. This ambiguity according to Quappe & Cantatore (2007) is the source of misunderstanding as well as misinterpretation. The language the international executives speaks or the nonverbal they use, vary depending on the myriad factors some of which have been discussed above. Nevertheless, this language is depended on one’s cultural background notes Rosen et al., (2000). International executive involved most frequently in the negotiations should understand cultural factors in the pursuit of the business success. Improving cross-cultural competency, therefore, lies at the heart of organisation success concur Yamazaki and Kayes (2004). According to McCall and Hollenbeck (2002), intercultural communication competence can be improved through several ways that include;

As Managers one needs to negotiate through a proper cultural perspective that do not prejudice or demean others. For instance, American and Europeans are linked with low-context cultural behaviours (Hall, 1973). This means that the western negotiators would wish to go straight into the business without wasting time delay. These cultures also value merit and expertise and always rush during negotiations. Wang (2005)notes that negotiating in such kind of a context requires the managers to prove their expertise first and gives minute focus to personal rapport. The opposite is true for the case of Eastern Asians nations their high context cultural values stress for building trust and relationship first before sitting down for proper negotiations. Negotiation in East Asia is more of ritualistic (Graham and Lam, 2003).

Another way, through which cross cultural communication competency can be improved, is through opening up to new ideas and appreciating difference cultural diversities (Duffy et al., 2004). However, this requires a manager who is keen at listening and talks less and also shows honesty and trust to the team he is working or negotiating with (Griffith, 2003). Managers can improve on these by attending social functions after work and during weekends, get involved or sponsor cultural awareness within the Organisation. (Hofstede, 2009), concurs with this assertion and emphasise that the social function improves managers cultural comprehension of diverse groups and at the same time engenders respect for one another.

According to McCall & Hollenbeck (2002), the manager could as well decide to improve his communication competency and that of his team through providing educational and training chances. By organizing for groups to attend educational training in foreign languages and provision of rotational programs at work, the manager sends signal that they value diversity and would the extra mile of inculcating it in the Organisation’s Culture (Yamazaki & Kayes, 2004). This can also be an excellent platform for the international executives to build relationships, spend time, listen and participate in other cultural activities. Consequently, managers enhance their cross-cultural communication competence and that of their teams (Yamazaki and Kayes, 2004).

Cross-cultural communication competency could also be improved through a better understanding of the language of space. As Hall (1973) warns, failure to understand the language of space could lead to cultural shock. Leading other or doing business in a foreign land could be extremely difficult. In Latin America or East Asia international executives are required to execute business in one’s intimate space. While some cultures are comfortable with this, this demesne evokes hostility as well as sexual feeling in US (Hall, 1973).

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

3.1 Introduction

The aim of this research is to study the impact of cross culture intelligent on international business negotiation and how it can contribute to the negotiation success by interviewing three different Garment Company including Bosideng, and Dayang Group and Youngor Group from China. Based on this aim, this section of the research seeks to provide discussions of the chosen research methodologies. Critically discuss the techniques of research such as the research philosophy, approach, strategy, design and resreach instruments. Moreover, the techniques of data collection and analysis are discussed here. To conclude this chapter three, the methodological limitations as well as strategies to ease such limitations are discussed.

3.2 Research philosophy

Research philosophy describes the way in which researchers use their autonomous opinions in formulating new ideas and knowledge regarding a specific research question (Saunders, Thornhill, and Lewis, 2009). According to Dilley (2004), researchers rely significantly on their choice of the research methods in agreeing to the underlying assumptions of method of research chosen. The relevance of research philosophy is therefore identified in provision of assumptions that guide the formulation of knowledge and provide differing perceptions into various constructs. Academic research in the area of businesses is normally conducted using two main philosophies that include positivism and interpretivism. While positivism is cantered on identification of the causal relationship in a study, interpretivism is relevant in providing descriptions to understand various phenomena from the basic incorporation of personal feelings and independent interpretations (Johnson and Clark, 2006).

Fundamentally, positivism results in attraction of objective perspectives which are supported by the use of mathematical methods of data analysis, thereby inclining a research towards non-biased deductions. Effectively, the researcher in positivism research does not influence the results if the research and neither does the research process influence the researcher in the quest to producing law like and generalisable deductions (Remenyi et al., 2003). However, interpretivism with its reliance on personal experiences, viewpoints, and feelings to explain the research phenomena, results in subjective deductions that are arrived at through qualitative analysis of data. The researcher is an integral part of the research process, hence inseparable to the research, since data collection depends on the ability of the researcher to observe behaviour of research objects, interpret the meaning of the social realities, and form judgements from the object’s experiences (Johnson and Clark, 2006).

Following the above understanding, this research utilised interpretivism research philosophy. This was underscored by the nature of the research that sought to understand how cultural differences influenced international business negotiation in the UK and China. To gain this understanding, the researcher would rely on the descriptions of the managers’ experiences in business negotiations in UK and China, interpret their viewpoints on negotiations across cultures, and formulate deductions without utilisations of any scientific techniques. Through interpretivism philosophy, the researcher adopted an empathetic position in seeking to analyse the influences of cultural differences and managers’ cultural intelligence of different cultures in business negotiations. As such, through the empathetic position, the researcher increased the probabilities of understanding the different levels of cognizance of different cultures among the managers and subsequent effects on business negotiations in the UK and China. Conversely, interpretivism inclined the research to greater risks of uncertainty due to the reliance on personal experiences, subjective observations, and interpretation of data.

3.3 Research approach

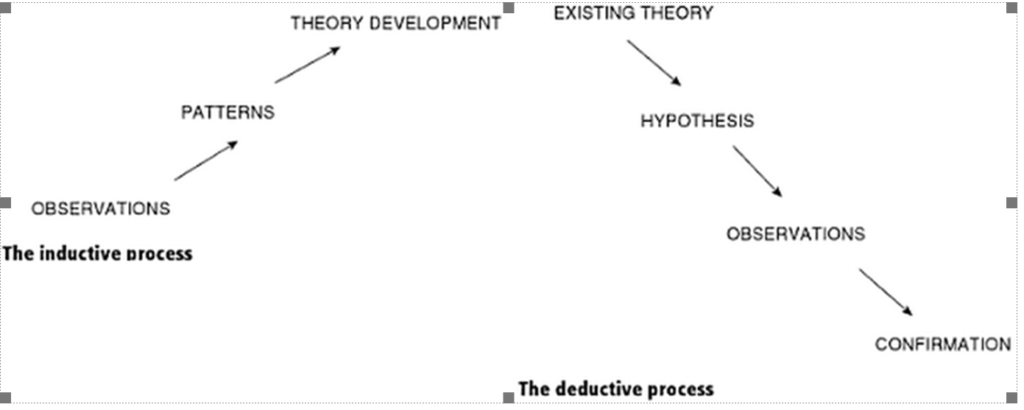

To effectively gain relevant knowledge in academic research, researchers are guided by their choice of the research approach. Saunders, Thornhill, and Lewis (2009) proclaim that the success of the developing knowledge using the research philosophy depends on the correct choice of the research approach which must be synonymous supporting the assumptions of the research philosophy. Inductive and deductive approaches are the commonly utilised approached in academic research.

On the one hand, inductive approach is identified from its emphasis on development of knowledge from the specific considerations and later using the general ideologies (Gill, Johnson, and Clark, 2010). This methodology is commonly but informally referred to as the bottom- up approach, whereby any relevant deductions are consequent of the pattern in research identified with close considerations of the premise in research. On the other hand, deductive approach connotes a kind of reasoning and knowledge development that begins from a broad perspective and narrows down to considerations of the more specific perspectives (Gill, Johnson, and Clark, 2010). Deductive approach uses a logical process in research that necessitates a researcher to develop insights through the top-down approach and utilising scientific premise in explanations (Saunders, Thornhill, and Lewis, 2009). Important to note, is that deductive approach is confined to five main stages that include, deducing hypotheses, operationalizing the hypotheses to provide explanations of the causal relationships, testing hypotheses, examining the results, and altering the results in order to fit if need be (Robinson, 2002).

Figure 3-1 Inductive and deductive processes

Source Burns and Burns (2008)

This research used inductive research approach. This was underscored by the researcher’s need to develop theory and disregarding the need for hypotheses or testing hypotheses. The research objectives did not feature any relationship between independent and dependent variables; hence, there was no need for pursuance to understand any causal relationship. On the contrary, inductive approach provided suitable chances of understanding the influences of cultural differences in business negotiations from specific issues of managers from the UK and China, as well as the observation of developing patterns in their explanations despite the overriding cultural diversity. Moreover, the inductive approach allowed the researcher to obtain qualitative data that was utilised in explaining the complexities of cultural differences and influences on business negotiations. This was entirely based on the participant’s perspectives and their cultural intelligence.

3.4 Research strategy

According to Remenyi et al. (2008), research strategy refers to the methodical research procedures that guide a research into achieving its objectives. The right choice of the research strategy determines the consistency of the research since the assumptions of the research philosophy have significant influences on the research strategy (Johnson and Clark, 2006). The basic reasons for the emphasis on the right choice of the research strategy relates to the need for the researcher to maintain steady focus on the research objectives throughout the research work and utilising correctly the available resources (Collis and Hussey, 2003). Just to list a few, case study, ethnography, and surveys are the commonly utilised research strategies (Saunders, Thornhill, and Lewis, 2009). Multiple case studies were utilised in this research. This entailed the consideration of three companies; Bosideng and Dayang Group and Youngor Group both from China. Observing relevant support for the use of multiple case studies in past literatures, the researcher identified that multiple cases increased the generalizability of the findings in the aspects of cultural intelligence and business negotiations across cultures. Moreover, the consideration of multiple cases in the research was essential in increasing the compelling ability of the research findings as well as increasing the robustness of the research. However, using multiple cases did not lack its limitations that included increased demand for extensive resources including time and finances.

3.5 Research design

Hanson and Grimmer (2007) identified that the choice of the research instrument is one of the most significant considerations in research processes. The success in collecting data from research participants directly influences the extents to which research offers credible findings. Imperatively, the research utilised semi-structured interviews to garner data from the three companies’ executives. The researcher interviewed a total of six managers from the three companies. Two managers were included in the interviews from every company. The researcher argued that six managers would present a viable account of the cultural experiences in international markets and the manager’s cultural intelligence with respect to how it influenced the success of the negotiations.

However, it was important to why the researcher chose semi-structured interviews. Firstly, the increased ability to probe for more information and clearer answers through semi-structured interviews provided impetus to their use (King, 2004). Secondly, semi-structured interviews reassured the objectivity of the research findings as participants were relaxed and held suitably high freedom that encouraged them to offer appropriate and true responses (Saunders, Thornhill, and Lewis, 2009). In order to increase the efficiency of the semi-structured interviews, the researcher ensured that the interviews were designed with close observation of the relevant procedures that helped in confirming high efficiency. These rule included elimination of ambiguity in the questions whereby each question asked specific details regarding either the cultural intelligence or the influences of cultural diversity on negotiations. Moreover, the researcher ensured that the interviews contained easily comprehensible language and statements. The semi-structured interviews were designed on the basis of cultural and values difference theory and communication theory.

During interview design, the researcher should first design an interview outline according to the research objectives and research questions before starting the interview. When designing the interview outline, the researcher should pay attention to the following issues: The researcher should design interview questions focusing on the research objectives in order to better address the research objectives and research questions; the interview questions should be controlled within 14 in order to prevent that the respondents may have the sense of resentment or boredom; it had better avoid sensitive words in the interview questions; the interview questions should not involve personal tendency of the researcher, and the researcher is not allowed to lead the respondents to answer the interview questions; the interview questions should be as open as possible, not restrict the respondents’ thinking, and allow the respondents to give a variety of information feedback.

Taking into account the above questions, the researcher has designed a general framework of the interview outline shown in Table 3-1. The specific interview questions can be seen in Appendix 1.

Table 3-1 Framework of the interview outline

| Research Objective | Interview Questions |

| Demographic Data | Qi – Qiv |

| To analyse the impact of the difference of national culture and values on international garment business negotiation | Q1-Q11 |

| To analyse the impact of cross culture communication styles on international garment business negotiation | Q12-Q13 |

3.6 Processes of data collection and analysis

The research will emphasize on qualitative data as opposed to quantitative data which is data collected in small amount but have higher quality which can represent a subject in deep method. Qualitative data technically encompasses in-depth discussion and descriptions of the observable events, participants thoughts, experiences and insights (Mujis, 2004). One very important implication of using qualitative data in research is that it results in highly subjective information as seen with the involvement of participant’s thoughts, ideas, experiences, and attitudes.

However, quantitative research relates to the research that demystifies concepts through garnering mathematical data that is then analysed using statistical descriptive means such as, the implementation of Microsoft Excel (Mujis, 2004). Importantly, quantitative data is essential in answering questions that seeks to show how many, how much and how frequent. As such, quantitative research allows researchers to exactly measure variable in a research.

The main reasons leading to the choice of qualitative research included, the complexity of the subject matter (cultural intelligence) which would not have been answered using hypotheses that are centered on yes or no questions (Saunders, Thornhill, and Lewis, 2009). Moreover, the qualitative research was chosen due to the fact that meaningful results would be achieved using the small sample size (Remenyi et al., 2003). Important to note is that qualitative research is not reliant on the sample as opposed to quantitative research. The primary data will be collected by interviewing 6 international garment business managers. As researcher have relative and also friend who work in the research subject industry, researcher can get informed to the manager in the company by friend and also relative. Researcher will send letter to two of the company and the other two will get approval through telephone.

There are a total of six managers that will be interview in total. The sample population will be relationship manger, marketing and supply chain manager in Bosideng (the Chinese subsidiary), Dayang Group, and Youngor Group. The research have rational of choosing the interviewee as relationship manager, marketing manager and supply chain manager as they are the people who will negotiate with other for sales, supply and also relation maintenance between business.

In order to ensure the interview quality, the researcher specifically applied for an unoccupied conference room respectively from four of the company to conduct one to one interview with the interviewees, to avoid being disturbed. In the interview process, the researcher promises that he will not interrupt the interviewees randomly or control the interviewees’ thought when they are answering questions, and the interview will not involve any personal privacy and company secret. Meanwhile, the researcher will also raise some questions related to the research objectives in accordance with the interviewees’ answers in the interview process. When the interviewees are answering questions, the researcher should not only pay attention to listen to them, but also record the interviewees’ answers timely and accurately. In order to record the interview information timely, the researcher can also use shorthand or marked way they can understand. After the interview, the researcher should express thanks to the interviewees promptly. For example, the researcher can give small gifts to the interviewees to express gratitude.

3.7 Data analysis method

Content analysis is a method to decide the existence of fix characters, words, phrases, sentences, concepts, or themes with the range of texts or sets of texts (Griffiths & Stotz, 2008). Therefore, content analysis is adopted in this research to analyse the feedback information collected from the interviewees. In order to make a content analysis on a text, the text should be coded or broken down into manageable classifications on a number of levels – word, word sense, phrase, sentence, or theme (Fisher, 2010). So this research will collate, code and classify all the collected data systematically. For example, all of the manger will be recorded as A, B, C, D, E and F to make the research clear and also increase the efficiency of research. Secondly, each of the interviewees’ answer should be placed under the corresponding questions. Thirdly, the research needs to analyse the main information recorded in the interview and extract the key words or sentences of the main information. Fourthly, the research also needs to make in-depth analysis of the key words or sentences, compare, analyse and summarise all the viewpoints, and finally obtain the research conclusions.

3.8 Research ethics

The research maintained some ethical considerations, which included asking for the general management’s consent to include the respective companies in the research. Furthermore, the participants were contacted through emails to request their acceptance to be involved. After consent was offered from the company general management and the participants, the researcher categorically, reassured the participant that the information garnered in the research would be used for the sole purposes of the academic research. Besides, the researcher made promises that the information would be protected and stored in the university library whereby access would be limited to persons authorised by the research supervisor and the library management staff. This was essential in mitigating the potential risks of exposure to the companies and the participants (Saunders, Thornhill, and Lewis, 2009).

Furthermore, the data that had been use in the research had to be valid to ensure the validity of the research. Therefore, it is fairly importance for researcher to ensure the data use is valid. Besides that, it is necessary for researcher to prove the validity of their research. So data used in the research and data collected for the research need to be reliable. To ensure the hypothesis inducted from theory is usable and valid to the current business and organization. The data used must not be expired (Chik weche & Fletcher, 2012). Researcher will intend to use resources that are in 10 to 15 years maximum to ensure the data is up to date except for theory and explanation of certain theory. To ensure the quality of the primary data that collected in the research, researcher need to go through all the data that collected and choose only answer which can reflect thinking and nature of the subject that been study.

3.9 Limitation of the research

The relevant limitation was the shortage in literatures connected to cultural intelligence. The researcher observed that this shortage was created by the low number of researches done on cultural intelligence and its impacts on business negotiation. In order to combat the limitation, the researcher embarked on readily searching for previous supporting material from credible sources, as well as probing to realise maximum benefits of interviews in the research. Besides, the researcher was limited in term of research resources that included finances and time. To solve this problem, yet assure the success of the research, the researcher implemented various strategies including visitations to the companies via public means and during off pick hours when the fares were low. Moreover, the researcher visited public libraries to access usable materials at low costs.

Chapter 4: Data Presentation and Analysis

4.1 Introduction

This study selected six managers of well-known international Chinese garment companies in order to carry out in-depth interviews. The managers were selected from three different clothing companies which included Bosideng, Dayang Group and Youngor Group. Two interviewees were selected from each company’s different departments which ranged from relationship manager, marketing manager and supply chain manager. These categories of managers were chosen as it was noted that they were frequently involved in negotiations for sales, supplies and also for maintenance of relation between businesses. Besides, the selected companies were deemed the most appropriate as it was noted that they frequently engaged with business partners from other cultures such as the UK. The selected companies majorly have very strong business ties with the several UK companies.